A goddess emerges from her bath, fully naked. The viewer observes her from a vantage point, and walks around to face her. Instead of being struck blind or transformed into some sort of beast for his transgressions, he manages to enjoy his voyeurism and walk away unscathed.

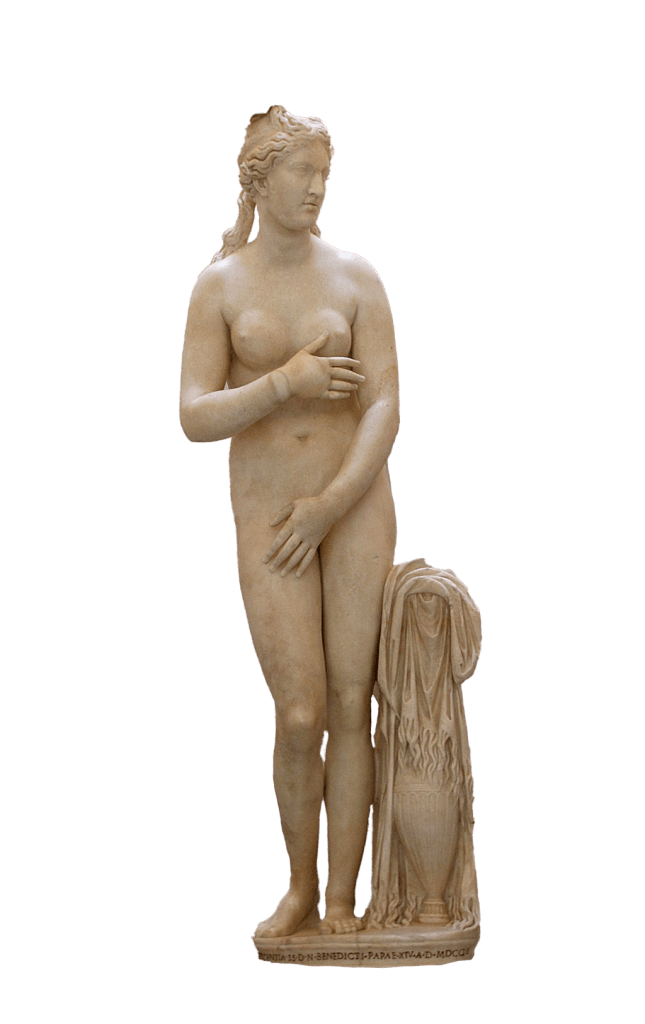

When Praxiteles’ sculpture of Aphrodite was displayed in the sanctuary of Knidos in the 4th century BC, it marked the first known life size, fully-nude sculpture of a woman in Greek art.1 She may have been displayed in a round room,2 where observers surrounded, appreciated, and viewed from every angle. Though the original has not survived, many replicas in marble and bronze captured the initial composition.

“The statue was universally admired for its perfection and unearthly beauty, and the story was told that such was its fame that the goddess herself paid a visit. “Where did Praxiteles see me naked?” she was rumored to have exclaimed.” – Keith Christiansen for the Met Museum3

Aphrodite stands as an idealised female figure.4 She holds a hand over herself, covering her genitals demurely. With the other hand she holds her clothes over a vase (an important load-bearing detail to distribute the statue’s weight) presumably just beginning to bathe, or just finishing. In some interpretations, such as the Capitoline Venus,5 she holds both hands over both her pubis and her breasts. In many of the recreations, she looks off to the side with a slightly downcast gaze. One could interpret her expression as almost embarrassed.

These compositional details may have been faithful to the original, or perhaps the Romans decided to make Aphrodite less sure of herself, more embarrassed, to reflect their own thoughts regarding female modesty and sexuality.6

Female nudity was previously reserved primarily for sex-workers.7 Despite Aphrodite being the goddess of love and desire, her nudity was not the norm. Male nudes on the other hand, abounded. From the archaic kouros8 to the classical period, they celebrated the idealised male form in powerful and heroic stances. Take the Artemision Zeus (or Poseidon) statue for example. The god is in action, striding and holding something aloft, perhaps a thunderbolt or a trident,9 depending on which god he was meant to represent. This god is in control of his actions, his surroundings, and feels very different to our Aphrodite.

A long history of objectification of women means statues like Aphrodite of Knidos were sexualised in both antiquity to today. There are stories of men who sought to express their enthusiasm over it.10 Today, Lely’s Venus is sitting behind barriers11 in museums due to excessive touching from visitors. Molly Malone’s statue in Ireland has discoloured breasts, from frequent passerbys’ hands.12 The female form does not exist in a vacuum and its reception is shaped by patriarchal attitudes.

Her stance has been a matter of debate, between erotic and modest.13 Is she not covering her genitals, but instead gesturing suggestively? Perhaps she is both. Is it in fact, her perceived modesty that makes it erotic? Taking a bold leap into what could be an arguably taboo depiction of the divine (with Cos, in fact, turning down the nude in favour of a clothed version). Despite desire being her domain, the gap could have been bridged by making Aphrodite seem less in control.

Does she retain her dignity in Classical Greek eyes by being slightly uncomfortable?

Greek women of the 4th century functioned within very narrow margins of acceptable behaviour, especially in regards to chastity and modesty. After all, we assume that Penelope is under a great threat from Odysseus if he suspects infidelity, despite his own extramarital affairs. Would depicting a goddess breaking those conventions be too far? In her modesty, the Aphrodite of Knidos instead becomes objectified, something to project desire onto, rather than show someone with ownership of their own sexuality. Does that make her more appealing in the eyes of the audience she was intended for?

Other female deities cast interesting questions in contrast. Depictions of Athena and Artemis break female gender roles by being powerful, active, and holding agency. One major differentiator may be that Athena and Artemis are committed to chastity.

Though we can speculate, we are not reacting to the original. We cannot know for sure, but one thing we can seek to understand is the reaction the viewer has to her.

Slightly tangentially, I’d like to recall the public reaction to the image of Marilyn Monroe’s iconic subway grate photo.14 Her white dress billowing upwards, like Aphrodite she also uses her hands to maintain her modesty. However, she has a carefree, cheeky expression as she laughs, and this image solidified her reputation as a sex symbol. There is a tension between the performance of modesty, and projected sexualisation.

I wrote this for fun! I’m interested in the intersection between material goods, in this case sculpture, and the many ways they reflect the social mores of the cultures they were made in. Additionally, the ways we react and interpret and how they reflect our current biases and beliefs.

Images are the Ludovisi Knidian Aphrodite and the Capitoline Venus.

- Macnab, Teresa, ‘The male gaze made marble: The Aphrodite of Knidos by the Ancient Greek Praxiteles’, The Art Story, (2021), <https://www.theartstory.org/blog/the-male-gaze-made-marble-the-aphrodite-of-knidos-by-the-ancient-greek-praxiteles/> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- ‘Tivoli and the Aphrodite of Venus’, <https://penelope.uchicago.edu/encyclopaedia_romana/greece/hetairai/tivoli.html> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Christiansen, Keith, ‘“Where did Praxiteles see me naked?” Depictions of Venus in Sixteenth-Century Italian Painting’, The Met Museum, (2018), <https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/venus-in-sixteenth-century-italian-painting> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Sorabella, Jean, ‘The Nude in Western Art and its Beginnings in Antiquity’, The Met Museum, (2008), <https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/the-nude-in-western-art-and-its-beginnings-in-antiquity> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Zucker, Steven and Harris, Beth, ‘Capitoline Venus (copy of the Aphrodite of Knidos)’, Smart History, (2016), <https://smarthistory.org/capitoline-venus-copy-of-the-aphrodite-of-knidos/> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Joseph, Kathryn, ‘Pudicitia: The Construction and Application of Female Morality in the Roman Republic and Early Empire’ (2018) <doi: https://doi.org/10.48617/etd.919> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Herring, Amanda, ‘ War, democracy, and art in ancient Greece, c.490-350 B.C.E.’, Smart History, (2022), <https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/war-democracy-art-ancient-greece/> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Getty Museum Collection, ‘Kouros’, <https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103VNP> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Harris, Beth and Zucker, Steven, ‘Artemision Zeus or Poseidon’, Smart History, (2014), <https://smarthistory.org/artemision-zeus-or-poseidon/>. [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Macnab, Teresa, ‘The male gaze made marble: The Aphrodite of Knidos by the Ancient Greek Praxiteles’, (2021). ↩︎

- University of Warwick Department of Classics and Ancient History, ‘Freeing Venus: The Aphrodite of Knidos’, <https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/warwickclassicsnetwork/publicengagement/studentengagement/storiesofobjects/blog/louisa/> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- BBC News, ‘Molly Malone statue “violated” by groping, says campaigner’, (2025), <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c07z2pxejyxo> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Cartwright, Mark, ‘Women in Ancient Greece’, World History Encyclopedia, (2016), <https://www.worldhistory.org/article/927/women-in-ancient-greece/> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

- Desta, Yohana, ‘The Untold Story Behind an Iconic Marilyn Monroe Moment’, Vanity Fair, (2017), <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/01/marilyn-monroe-rare-footage> [accessed 13 April 2025]. ↩︎

Leave a comment